So far in this series of posts we have talked about the history of .NET versioning, targeting different .NET Framework versions and library versioning in .NET. Now for the final piece of the puzzle: Building NuGet packages that target multiple .NET Framework versions.

NuGet packages

First we need to understand what NuGet packages look like under the hood. These files with the .nupkg file ending are actually ZIP archives with a specific layout of files and directories inside.

You’ll find an XML file with the ending .nuspec with metadata such as name, version and dependencies. Next to this file there are directories with names like lib and content for things like binaries and resource files. The NuGet documentation provides a nice overview on how to create a NuGet package with this structure from a convention based working directory.

Within the lib directory a NuGet package can have subdirectories for different .NET Framework versions. For example a package might contain lib\net20\MyLib.dll and lib\net35\MyLib.dll. For more details on this mechanism take a look at NuGet’s documentation on Target Frameworks.

Now that we know where to place binaries for multiple frameworks in a NuGet packages, let’s find out how to actually build them. We saw the Visual Studio dialog for selecting a target framework in the first post of this series:

Unfortunately you can only select a single framework here. If you wish to build our source code for multiple frameworks you can to choose from a number of alternative options: shared projects, the new project.json format and manually customizing build configurations in .csproj files. Lets look at pros and cons for each.

Shared projects

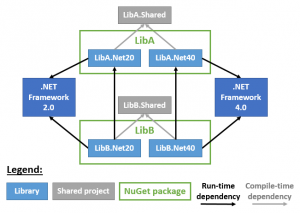

Visual Studio 2013 Update 2 introduced a new project type called “shared projects”. This was orginally intended for Universal XAML apps but the possible applications reach far beyond that. These projects contain C# or VB.NET code like regular projects but cannot be compiled by themselves. Instead then are referenced by regular projects which then act as if all files from the shared project were copied over. This means shared projects act as compile-time rather than run-time dependencies.

Note that this is not the same as statically-linked libraries, since the entire source tree is built separately for each referencing project, possibly with different compiler options. This enables you to create individual projects for each framework you wish to target while still keeping the source files all in one place. However, you need manage any dependencies (NuGet or otherwise) independently for each project. If your solution already consists of multiple projects multiplying these by the number of frameworks you wish to support can result in an unwieldy number of projects and references between them.

project.json

Along with the .NET Core project Microsoft also introduced a new build system. While this system is mainly intended for .NET Core it also supports targeting the traditional .NET Framework versions.

This build system is centered around a file called project.json. This file allows you to specify one or more target frameworks. NuGet dependencies can be associated with specific frameworks or shared across all frameworks. For example, a project targeting the .NET Framework 4.5 and 4.6 with a dependency on LibA for both and on LibB only for 4.6 would look like this:

{ "dependencies": { "LibA": "1.0" }, "frameworks": { "dnx45": {}, "dnx46": { "dependencies": { "LibB": "1.0" } } } } |

The ability to target multiple frameworks from a single project is a major maintainability benefit. Especially the fact that common dependencies can be specified in a single location greatly reduces complexity. However, the project.json format is still very new and plans to replace it are already in the works: See the article Changes to Project.json in the .NET Blog.

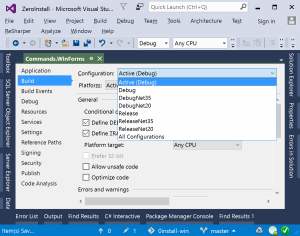

Build configurations

Visual Studio allows you to create multiple build configurations for a project, with Debug and Release being the default. The project property panes have a drop-down box at the top that allows you to specify for which build configurations you wish to apply your changes. However, some settings, such as the target framework, can only be set for the entire project.

In the underlying .csproj files, which are interpreted by MSBuild, these build configurations are expressed like this:

<propertygroup> <assemblyname>ZeroInstall.Publish</assemblyname> <targetframeworkversion>v4.0</targetframeworkversion> </propertygroup> <propertygroup condition="'$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Debug|AnyCPU'"> <debugsymbols>true</debugsymbols> <checkforoverflowunderflow>true</checkforoverflowunderflow> </propertygroup> <propertygroup condition="'$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Release|AnyCPU'"> <debugsymbols>false</debugsymbols> <checkforoverflowunderflow>false</checkforoverflowunderflow> </propertygroup> |

As you can see, individual settings are grouped into <PropertyGroup>s which can carry Condition expressions. While Visual Studio always uses the same fixed groups and conditions, you are free to create your own combinations in a text editor. Even if you create constructs Visual Studio does not know how to express in the GUI, most features, including compilation, will continue to work fine. However, modifying the corresponding settings in the GUI may longer work properly.

So to get past Visual Studio’s limitation of one target framework per project:

- Create new build configurations like

ReleaseNet20andReleaseNet35in Visual Studio. - Open the project file in a text editor.

- Remove

<TargetFrameworkVersion>from the fist<PropertyGroup>. - Add

<TargetFrameworkVersion>s with different values in the configuration-specific<PropertyGroup>s.

When referencing a library that provides multiple framework-specific builds (like the we one we are building!) NuGet selects the best-suited binary at build-time. Unfortunately this mechanism does not automatically handle constructs like the one described above, so we need to take care of this manually:

<itemgroup condition="'$(Configuration)'=='ReleaseNet20'"> <reference include="Newtonsoft.Json"> <hintpath>..\packages\Newtonsoft.Json.9.0.1\lib\net20\Newtonsoft.Json.dll</hintpath> </reference> </itemgroup> <itemgroup condition="'$(Configuration)'=='ReleaseNet35'"> <reference include="Newtonsoft.Json"> <hintpath>..\packages\Newtonsoft.Json.9.0.1\lib\net35\Newtonsoft.Json.dll</hintpath> </reference> </itemgroup> |

All this is not officially supported in Visual Studio and requires manual editing of project files usually not intended for direct human consumption. However, it works reliably with MSBuild and allows you to keep the entire configuration for a project in a single location. We chose this method for multi-framework support in NanoByte.Common and Zero Install. Take a look at the ZeroInstall.Store project file for a representative example.

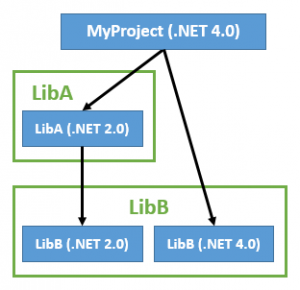

Transitive references and .NET Framework versions

In the previous post we learned that when you install a NuGet package the transitive closure of its dependencies also get installed. This ensures that the build output contains everything required to run the application. When installing such indirect dependencies NuGet still selects the binaries that best match the target framework of the current project, not necessarily the framework the library was compiled against.

Unlike name, version and public key the target framework is not part of an assembly’s identity. This means the CLR will not notice such an assembly swap at runtime. There is no need for special <bindingRedirect>s in the app.config/web.config file. Some portable libraries are intentionally designed to have one binary to be compiled against and other framework-specific libraries to link against at runtime. This is called the The Bait and Switch PCL Trick.

This concludes our series on .NET backward compatibility. Thanks for reading.